Large feral herbivores

Australia’s rangelands face pressure from large feral herbivores such as horses, donkeys and camels. These animals cause problems including overgrazing, destruction of trees and shrubs, and damage to infrastructure, as well as posing risks to people on the roads.

Camels in particular are a concern throughout central Australia. They were introduced to Australia from 1840 to help with inland exploration and by the late 1800s were well established as beasts of burden, carting wool bales and other goods across the interior. Cameleers were commonly known as Afghans or Ghans, although many of them came from India, Egypt and Turkey. As motorised transport took over in the 1920s, many camels were released into the wild, where they thrived.

A century later, feral camels have become a major environmental problem in arid Australia, which may have the largest wild camel population in the world. Highly mobile and with no predators, camels will eat more than 80% of plant species and cause damage to important bush food plants such as quandong trees by trampling them as well as eating them.

Able to smell water sources from up to five kilometres away, camels gather in large numbers when water is scarce, damaging infrastructure such as fences, taps and pumps in their search for a drink. Important water sources such as rockholes are often contaminated by the carcasses of dead camels, reducing water availability for people as well as other animal species.

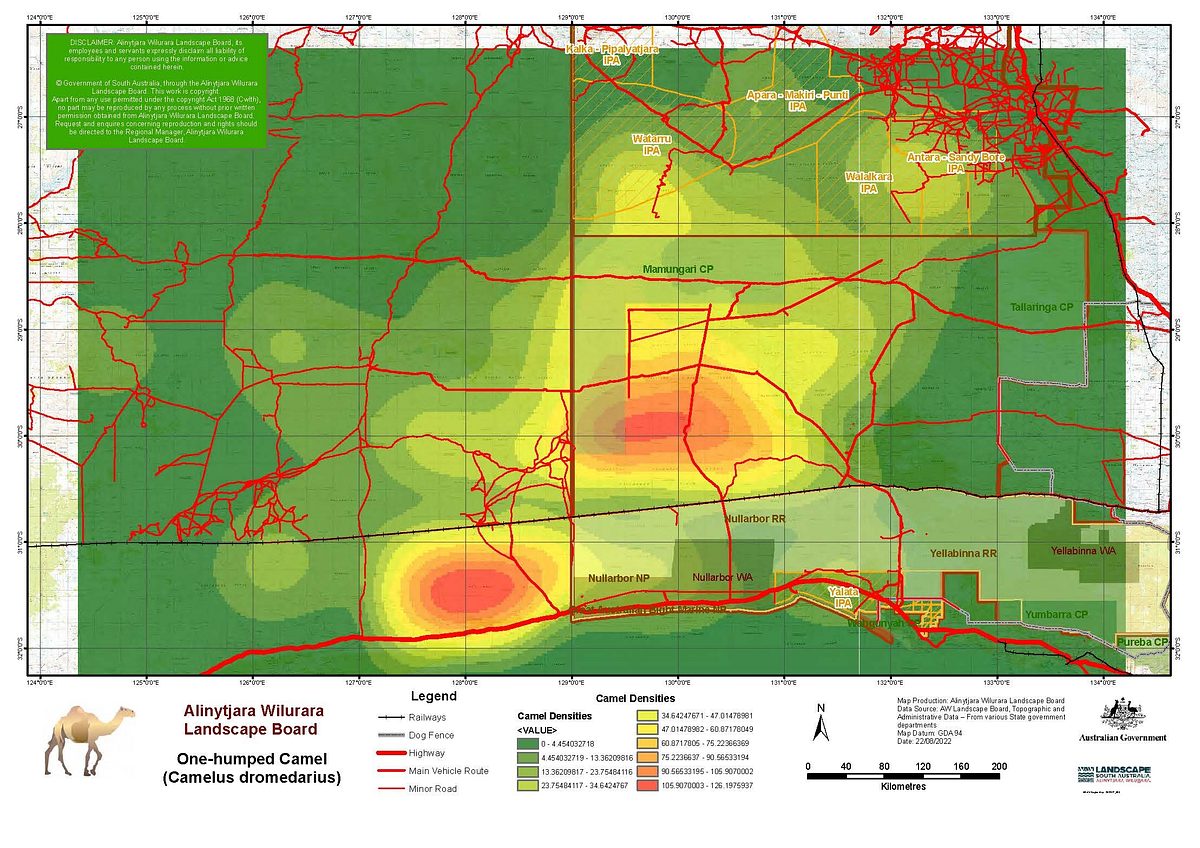

The Alinytjara Wiluṟara Landscape Board works with stakeholders in the region to monitor and control camels. In a ten-day operation in 2023, 17 camels were fitted with tracking collars. Skilled marksmen in helicopters used tranquiliser guns to immobilise the animals so the collars could be fitted. The collars are manufactured locally to AW’s specifications, including GPS beacons and enough batteries to power the collars for up to two years, providing up-to-date data about the camels’ movements.

Camel numbers rise when rains provide them with ample food, and culls have been carried out periodically to minimise the impact of these introduced herbivores on communities and native ecosystems. Data from the collars helps to focus the search for the animals.

The Alinytjara Wiluṟara Landscape Board supports camel monitoring and control with funding from the State Government’s Landscape Priorities Fund and the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program.